“No important change in human conduct is ever accomplished without an internal change in our intellectual emphases, our loyalties, our affections, and our convictions. In our attempt to make conservation easy, we have dodged its spiritual implications.” ~Aldo Leopold

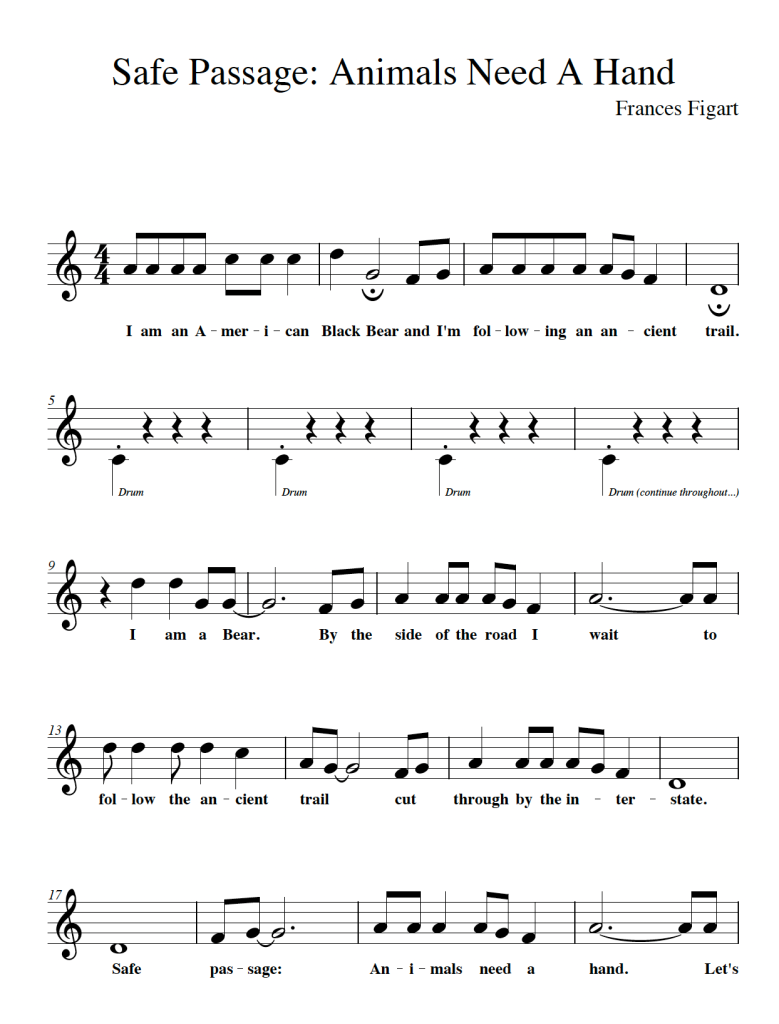

I have spent the better part of two years devoting energy to an effort to help wildlife more safely cross the highways in Western North Carolina and East Tennessee. I’ve worked alongside scientists to make their work more accessible to the lay public through branding, articles, a web site, social media posts, a children’s book, and even a music video.

Now I feel that this work to help allow bear, deer, elk, and many other species the right of way is partially canceled out by a shocking proposal to allow hunting with dogs in the Pisgah, Panthertown–Bonas Defeat, and Standing Indian bear sanctuaries in Western North Carolina.

“The bear sanctuary concept was based on knowledge of the smaller home ranges of female bears and dispersal behavior of young males,” says Mike Pelton, Professor Emeritus, Wildlife Science, University of Tennessee, whose groundbreaking research helped to modernize black bear management around the world. “Additionally, starting hunts later in the fall protected the females, skewing the harvest ratio toward males. Using knowledge of bear behavior for management strategies assisted in the recovery of the bear population. This success led to the dispersal of bears into new and nonpublic habitats.”

But now, increased populations of both humans and bears means that humans are going to be seeing more bears in developed areas. The wildlife commission wants to open these three sanctuaries to hunting to address this issue by killing off some of the bears. But not all bear “sightings” represent “conflicts.” Those who are not educated about living with bears are exhibiting panic behaviors and turning what should simply be a bear “sighting” into a de facto “conflict.”

We do not have too many bears; we have too little education.

“Campers must learn to store their food properly to keep from attracting bears,” says bear photographer Bill Lea, a retired U.S. Forest Service ranger who knows the bears in these three sanctuaries. “Hikers must learn proper behavior when encountering a bear while hiking. Nearby property owners must learn to eliminate the foods (bird feeders, garbage, barbeque grills, etc.) that are attracting bears to their property. The indiscriminate killing of bears is not the solution to resolving negative human-bear interactions. Education is the one and only effective answer.”

Pelton, who has 30+ years of experience in bear research, reasons that while these three well-established sanctuaries occupy a very small portion of the huge national forests, they provide important refugia for bears and are needed for the long-term stability and resiliency of this species.

“I am concerned that once sanctuaries are opened for hunting, it will be hard to ever reverse that action,” he says. “As we have all learned from the pandemic, no one can predict the future regarding potential negative impacts due to natural or human-caused events. Holding onto these three safe havens is insurance for possible future issues for bears.”

The fierce green light

The 1949 non-fiction masterpiece A Sand County Almanac by ecologist Aldo Leopold is one of history’s seminal testaments to the environmentalist ethic. One philosophy it espouses is the idea that without preserving some wild spaces, not only animals but humans themselves will no longer be free.

I can identify with Leopold and his rallying cry against policy makers whose pseudo-conservation efforts vainly mask their desires for economic gain. While our understanding of natural history has tumbled leaps and bounds ahead of where it stood in Leopold’s time—just before the advent of DDT and the subsequent writing of another conservation pioneer, Rachel Carson—our forests are rapidly disappearing, our rivers and oceans face ever more serious threats from pollution, and our planet is entering the sixth mass extinction of plants and animals. This is our own doing—and, from one human to the next, the magnitude of having passed the tipping point seems to manifest itself in denial, indifference, nearly unbearable emotional void, or a continuing struggle to attempt to reverse the needle, if only a tiny bit.

“In those days, we had never heard of passing up a chance to kill a wolf,” writes Leopold in his chapter “Think Like a Mountain.” As a mother wolf with injured pups scurrying around her dies at his own hands, he sees “a fierce green light dying in her eyes. I realized then, and have known ever since, that there was something new to me in those eyes—something known only to her and to the mountain.”

History shows that humans evolve at different rates. While some of us understand the value in conservation, others justify willful habitat destruction and species annihilation predicated solely on greed by falling back on the “man conquers nature” mentality that reigned in past centuries. We all want the same thing, ultimately, but it looks different depending upon the level of consciousness from which each of us is acting.

Whether they be mountains, forests, rivers, deserts, oceans, or bear families who have lived on safe havens in Southern Appalachia for 50 years, it is vital that we strive to champion, protect, and maintain the pristine state of what few natural landscapes remain in the areas around where we make our homes.

Leopold ends his chapter thus: “We all strive for safety, prosperity, comfort, long life, and dullness. The deer strives with his supple legs, the cowman with trap and poison, the statesman with pen, the most of us with machines, votes, and dollars, but it all comes to the same thing: peace in our time. A measure of success in this is all well enough, and perhaps is a requisite to objective thinking, but too much safety seems to yield only danger in the long run. Perhaps this is behind Thoreau’s dictum: in wildness is the salvation of the world. Perhaps this is the hidden meaning in the howl of the wolf, long known among mountains, but seldom perceived among men.”

We have to act NOW!

Please consider raising your voice to save unsuspecting bears in three North Carolina sanctuaries from a merciless, torturous, and ultimately senseless death. The deadline is tomorrow!

It’s really as simple as sending an email. Submit your comments by Monday, January 31, via e-mail at regulations@ncwildlife.org or by mail to Rule-making Coordinator, NCWRC,1701 Mail Service Center, Raleigh, NC 27699-1701.

Visit the Facebook page Protect Bear Sanctuaries to learn more about the issue or write to me directly for talking points.

Recent Comments